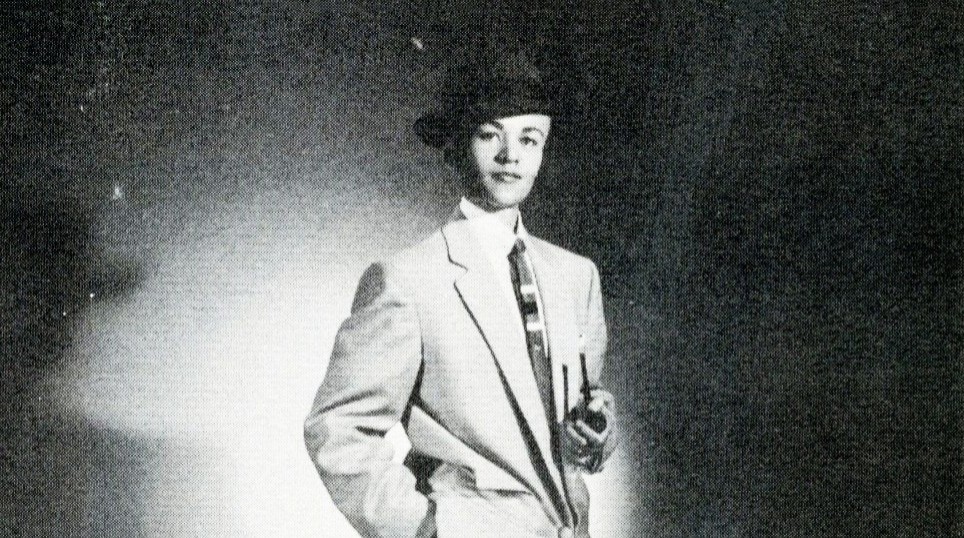

“I think part of the high for them and you,” Als said, “was the then-novel experience of a more or less straight white woman hanging out in a place she had no business being and finding the denizens, if not beautiful, then at least interesting. Als philosophized about why Arbus may have been so attached to people like DeLarverie. He mentioned, in particular, Arbus’s portraits of Storme DeLarverie, a mixed-race lesbian who became a leader for the gay-rights movement, and who Als had the chance to interview for the Village Voice. And that’s what you did-get in people’s faces.” The only three things in the room seemed to be Arbus’s ghost, Als, and his writing.Īls went on to talk about Arbus’s subjects-the marginalized people of Manhattan, “none of that Cartier-Bresson stuff.” Arbus kept her images spontaneous, and by that, she was doing something risky, Als said, “given that one’s survival, in part, depends on the understanding that New Yorkers crave attention, but will fuck you up if you get in their face. From where I was sitting, it was hard to ever see Als’s eyes-the lighting made it so that his essay was reflected in his glasses. “By addressing her as Diane, I’m bringing her life and work back to the idea of correspondence, the trading of one thought because it inspires another over the distance of time.”Īs Als said this, an image of Arbus, slightly blurred and plainly beautiful, was projected above him.

“Obviously, I’m using letter-writing as a kind of metaphor, but not in an Emily Dickinson, ‘Here’s my letter to the world that never wrote to me’ way,” Als said near the beginning. On to the essay, which was less a carefully structured inquiry than an interweaving of Arbus’s letters, Als’s personal life, and New York history. Still, she was Diane Arbus’s mother, and I bow down to her for that.” (Everyone stayed glued to their seats.) And then he had a quick word about his pronunciation of Arbus’s first name: “I pronounce Diane, ‘Dee-ann,’ the way her mother preferred-the French pronunciation-because she was a little pretentious. He gave another preface, warning that people interested in art theory should leave right away. “Because I’m a guilty person, I told him what I had done immediately, and he just laughed and laughed.” “I thought I could pay for my ‘entertainment’ by credit card,” Als said. Regen, the founder of Regen Projects, who died in 1998, was the namesake of the fund that supports this Visionaries talk. In one of the four brief prefaces to his essay, which is titled “Diane Arbus in Manhattan,” Als recounted renting pay-per-view porn on Stuart Regen’s credit card.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)